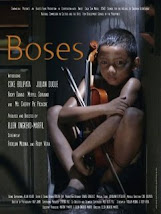

The Cast: Coke Bolipata, Cherry Pie Picache, Ricky Davao, Julian Duque

“Boses” is for the world

By Joel David Philippine Daily Inquirer First Posted 11:23pm (Mla time) 10/12/2008 MANILA, Philippines

It is not the first noteworthy film shut out of awards recognition in Cinemalaya history. “Boses” joins a long list of works overlooked upon initial release, whose rewards would come in the form of belated acclaim, discursive attention, extended shelf-life, or maybe all three. “Boses” also serves to indicate a peak in the Cinemalaya ideal: the hope that talent from the margins could overrun the mainstream while playing by the latter's rules. The movie takes a grim situation (child abuse) and matches it with high-art therapy (classical music). The narrative unfolds with a strong dose of pleasure, unexpected and startling in its effectiveness, given the nature of the material. Already the top grosser among the latest Cinemalaya crop, “Boses” appears capable of attaining blockbuster status. Repeat viewership is boosted by word-of-mouth commendation, occasionally hysterical responses even in staid venues that it has graced so far, and star-is-born adulation lavished on its gifted and charismatic child performer, Julian Duque.

Not perfect

To be sure, “Boses” is not a perfect film. A more radical handling of its material would probably have made us better understand, even empathize with, the abuser's dramatic condition and the child's reason for willing to remain a victim for so long. Those conversant with real-life accounts may suspect that the filmmakers sanitized the situation, not to mention the language, familiar to actual child-abuse perpetrators, victims, and therapists. Given all the ways it might have fallen short, is “Boses” the favorite of many Cinemalaya observers? One reason maybe that it is dedicated to Johven Velasco, a film artist, teacher, and scholar who spent a lifetime in the academe until his sudden, tragic demise a year ago this month, unknown to the rest of the world except for a handful of students and friends who swear by his selfless dedication and willingness to share everything he had. The fact that filmmaker Ellen Ongkeko-Marfil makes this connection between the lives of her characters and that of an actual acquaintance indicates that she upholds the power of love, a value that, even more than film pleasure, tends to upset film experts used to the facile ways it constantly gets exploited in the medium. Indeed, the core relationship in “Boses” between the young survivor of parental abuse and the violinist who awakens the former's talent (and, in the process, recovers from his own tragedy), provides the film's heartbeat. Not only does the interaction start cute and end intensely, with a near-breakdown and bittersweet separation; it also occasions bravura performances by the actors as thespians and as musicians.

Stage to film

Surprising, though perfectly logical, was Ongkeko-Marfil's acknowledgment, during one of the film's screenings that, in real life, Bolipata is Duque's violin mentor. Ongkeko-Marfil's background in stage arts has obviously helped the impressive evolution of her cinematic skills. With “Boses,” she hews close to what the late greats Lino Brocka and Ishmael Bernal misrecognized among indie filmmakers as foreign-festival and anti-mass audience innovators, struggled to achieve: an unapologetic catering to the viewers' pleasure alongside intelligent direction.

Melodrama, the mode that Ongkeko-Marfil has chosen, poses a grave challenge to serious film evaluators. The genre belongs to the larger group of “body” films, so-called for their ability to provoke corporeal, as opposed to cerebral, responses - goose bump-raising in horror, sexual arousal in pornography, laughter incitement in comedy and, in this instance, tear jerking. For the greater part of the last two decades, feminist critics have been spearheading a campaign to rehabilitate these much-derided genres, but their uphill movement shows no signs of reaching level ground in high-art culture, the indie-film scene included. “Boses” evinces a systematic working-through of the elements peculiar to local melodrama: kilig, tampuhan, tawanan, kantahan (with violins instead of voices), habulan, and pagwawala. The penultimate sequence between the teacher and student protagonists encapsulates the earlier depiction of the shifting nature of their interaction: from farewell bonding, to panic, to relief, to hysteria, to music-making, to a brief comic exchange, to a final display of exuberance. One might wish that the performers had been seasoned enough to allow Ongkeko-Marfil to use a single take, but the scene had unfolded in one continuous action, such was the brilliance of said sequence's nearly wordless conception, grand in romantic dimension yet sad in its recognition that the just-bonded individuals may never be this close, and this innocent, again.

Successful finale

The musical number that ends the narrative succeeds because it refuses to provide definitive closure for any of the characters. The teacher will have to contend with his newfound dependence on the validation provided by his prodigy. The child will have to work out his loyalties for two needy father figures. The biological father will have to face the reality of his son challenging his vulnerable manhood. The social worker will start worrying whether her decision to reconcile the family was right. A few films have helped incite revolutionary change, and the inward turn that “Boses” inspires ought to be fulfillment enough for the talents behind it. Most local digital practitioners will continue to aspire for, and attain, festival honors abroad, but this is the first movie made by a colleague of theirs that, more than anything else, truly belongs to the world because it remains rooted at home.

Julian Duque playing Springtime by Vivaldi

For older postings, see the archives on the right side of the screen

No comments:

Post a Comment